The First International Conference: Methodological Perspectives for the Study of Ancient Texts

发布时间:2017-04-24By Don Kuang (Renmin University of China), Callisto Searle (Renmin University of China)

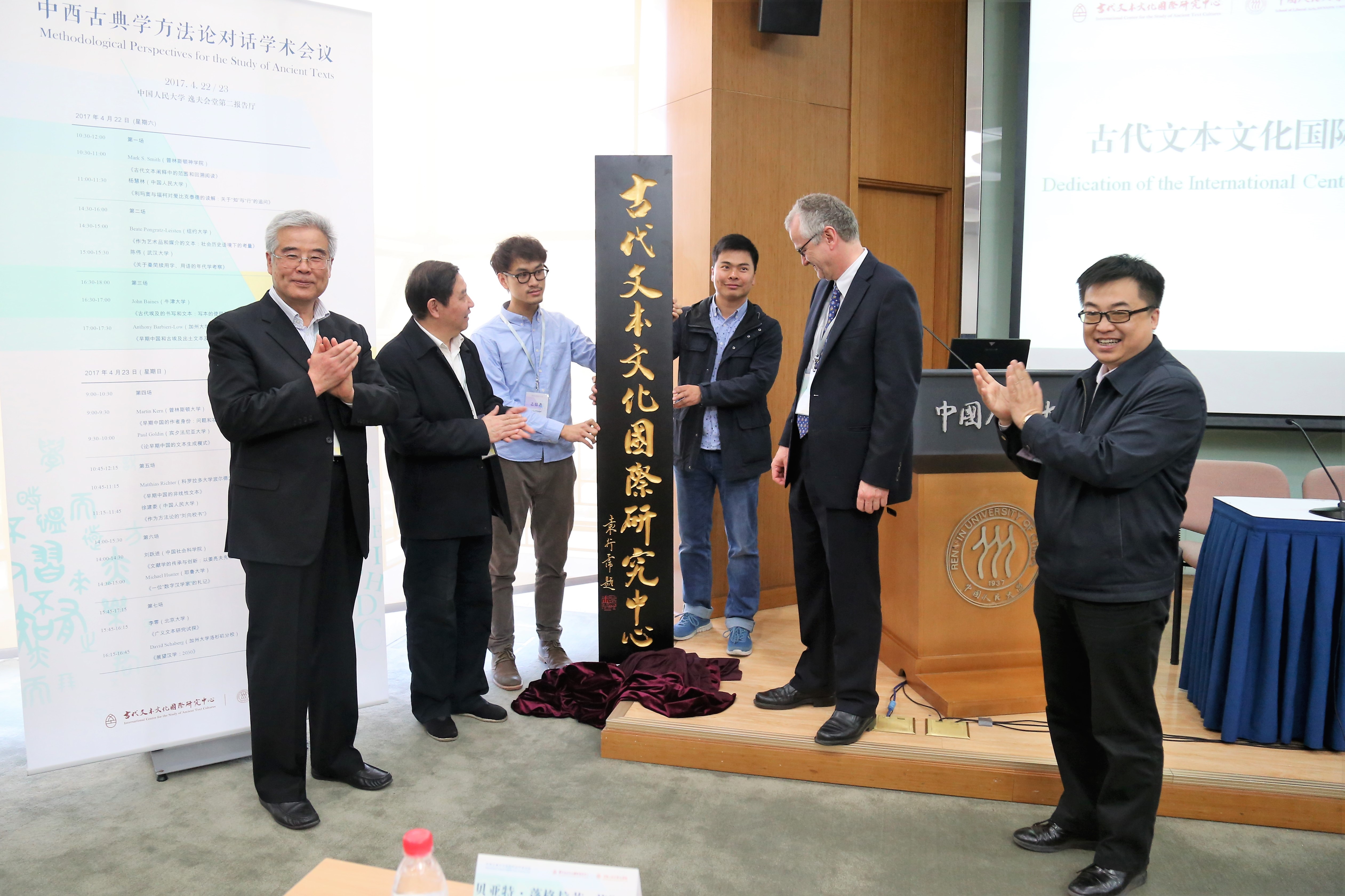

From 23rd -24th April 2017, the International Center for the Study of Ancient Text Cultures (Renmin University of China) hosted the first international manuscript culture conference on the theme of “Methodological Perspectives for the Study of Ancient Texts” at Renmin University of China in Beijing. More than ten distinguished scholars from the fields of different civilizations presented speeches on methodology of classical studies.

first session featured was Professor Mark Smith (Princeton University) and Professor Yang Huilin (Renmin University of China).

Professor Smith discussed the topic of scope and retrospective reading in interpreting ancient texts. Scope refers to any given writer’s scope of cultural information that she or he draws on in composing a text. He suggests that interpreters often read prior texts backwards or “retrospectively,” not only adding new concerns from their scope of texts but also introducing further layers of meaning with the aid of yet other texts. Authors themselves also induce retrospective reading within their texts, by constructing passages to be read in light of later parts of their texts and thus adding to the understanding.

Professor Yang presents that at the end of 16 century, Matteo Ricci translated Epictetus’ book Encheridion with commentary, a book entitiled The Book of 25 Paragraphs or 25 Sayings, to bridge the gap between the ethical education of the East and the West, whilst being sure not to challenge either Chinese tradition or Christian values. Despite the differing opinions of missionaries and Confucians scholars in China, Ricci actually offers a new interpretation of the Chinese traditional concepts of “Principle” and “Application” from Stoicism to Christianized Confucianism.

Professor Beate Pongratz-Leisten (New York University) argued in her presentation that rather than passive existence, the material existence of a written artifact is to be defined as the component of an object-agent-network in which the object is historically and culturally embedded in a particular context, which might be an institution, community, funerary context, private household, etc. In other words, an object “is meaningful by virtue of its relation to something beyond itself” by referring to its owner or recipient and by referring to its original producer.

Professor Chen Wei (Wuhan University) explains that the Qin dynasty was revolutionary with keen determination that it made frequent changes to names for administrative purposes. This practice can be proved and detailed by discovery of unearthed bamboo and wood manuscripts. He explores some of the phenomena of word usage and alternate graphs.

Professor John Baines (Oxford University) focused on writing on stone as a key example for comparative purposes. His principal case study was of the Pyramid Texts, which are first attested by fragments from a temple of the early 5th dynasty (ca. 2450 BCE), and as continuous inscriptions in the burial apartments of a pyramid from the end of the dynasty (ca. 2325).

Professor Anthony Barbieri-Low (University of California, Santa Barbara) looked at the problems of methodology and interpretation related to three categories of recovered texts from Early China and Ancient Egypt, namely interred texts recovered from tombs or temple deposits, discarded texts excavated from garbage pits and wells, and looted texts without any secure provenance or excavation context.

Professor Martin Kern (Princeton University) raised the questions of author and authorship of ancient Chinese texts, and underscored that textual fluidity of text should be a major concern in manuscript study. He explores why “imperial” texts became increasingly “authored texts,” and what were the specific factors that drove the emergence of “strong authors,” that is, historical figures in control of, and responsible for, their texts.

Professor Paul Goldin (University of Pennsylvania) explains that most recent scholarship on the problem of textual production in early China is identifying one particular mode as paradigmatic. He argues that although they have helped to establish the important point that single-authored texts are scarcely attested before the Han dynasty, they all ultimately fail because there was, in fact, a diversity of modes of textual production. He then surveys nine types of textual production, with reference to the particular texts that exemplify them.

Professor Matthias L. Richter ( University of Colorado at Boulder) addressed an aspect of early Chinese literature: different types of functionality of texts. Not all texts are best read as linear texts. He focuses on one particular text that interweaves historical narrative with technical text in a way that makes it unlikely that the audience took the product at face value, reading the technical text as direct speech uttered by figures in the historical narrative.

Professor Xu Jianwei (Renmin University of China) presented an ancient textual revolution in Han dynasty by Liu Xiang, a land-mark character that greatly changed the appearance of the early Chinese textual world by his compilation and editorial work, which was supported by the government. He believes that the current vision of the textual world of ancient China stems primarily from a constructioncreated by Liu Xiang.

Professor Liu Yuejin (Institution of Literature, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) suggested that modern scholars, compared to the previous group, are in a better position to continue the practice of traditional research because of the following reasons: more and more literature is being excavated, texts that have been abroad are being returned to China, and electronization of Chinese texts offers more convenient access to scholars.

Professor Michael Hunt (Yale University) makes use of digital database tools and other digital methodologies for the study of ancient Chinese texts, with a particular focus on the tools that enabled the comprehensive survey of early Confucian material. He also surveys the emerging East Asian digital humanities scene in North America and Europe to suggest ways in which students and scholars in China and elsewhere can work together to make the Chinese textual heritage more accessible to a wider audience.

Professor David Schaberg (University of California, Los Angeles) tried to pre-conceive how research will be done in the future based on observation in humanities disciplines and departments at UCLA and elsewhere to show how early China studies is situated with respect to them. Then he offered a methodological defense (with some critique) of interdisciplinary work, that is, reading historical, ritual, and essayistic texts with special attention to their literary dimensions—and with confidence that these literary dimensions, in addition to being beautiful in themselves, can help answer basic questions about the texts’ origins, use, and transmission.

Professor Li Ling (Peking University) distinguished the definition of “Text” from a universal level of literature and the narrow sense of “book”, that on different bases, different methods are required to begin the study. Then he discussed the relationship between textual study, history, literature and archeology. He also expressed concerns about the contentious dynamic of Chinese culture and points out the so-called craze for traditional Chinese culture is actually a reflection of the anxiety of identity and cultural lack of confidence deeply rooted in the Chinese nature, ever since the beginning of pre-modern China.