Canonical Texts and Commentaries

发布时间:2017-06-18Summary of the First Annual Graduate Student Workshop “Canonical Texts and Commentaries”

International Center for the Study of Ancient Text Cultures

Renmin University of China

Beijing, June 18th –24th, 2017

Author: Marcel Schneider, University of Zurich

Jing ZHANG, Renmin University of China

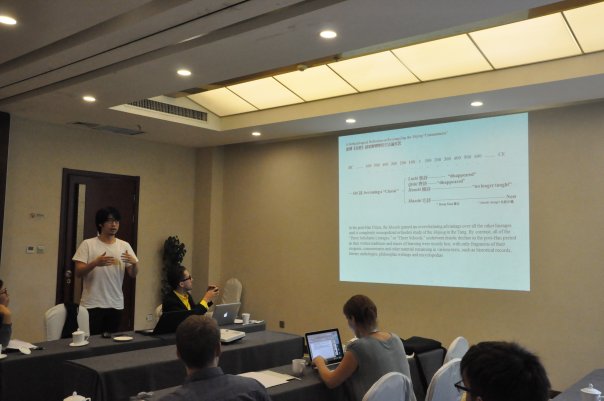

From 18-24 June 2017, the International Center for the Study of Ancient Text Cultures (Renmin University of China) hosted the First Annual Ph.D. Graduate Student Workshop titled “Canonical Texts and Commentaries” at the Nirvana Resort Hotel in Beijing. Four distinguishedprofessors from the fields of Chinese, Greek, and Roman antiquity presentedday-long lectures in English or in Chinese with simultaneous translation.

The workshop kicked off in the morning of June 19 with a welcome and introductory address by Prof. Martin Kern (Princeton University), the Director of the Center. Arenowned scholar of early Chinese history, literature and textual culture, Kern talked about the commentarial tradition in both transmitted and excavated texts, how texts accumulate over time, and what kind of hermeneuticalchallenges modern researchers encounter when dealing with them.Pointing out the limited emphasis on original authors in antiquity, but also the importance of ancient commentators and editors (including Confucius), Kern reviewed in detail examples from the Classic of Poetry (Shijing), the fountainhead of Chinese poetry and the most-invoked text in all of ancient Chinese literature.He stressed the importance of the Qin and Han imperial court scholars (boshi博士) for the formation of the Confucian Canon and discussed how already with the Shijing,the fundamentally political nature of Chinese literature was established. Introducing the concepts of “textual repertoires” and “composite texts,” and reflecting on the interplay of oral and written practices in the early transmission in the Chinese classics, Kern showed how a poem or song was flexibly shaped and recomposed according to the needs of particular times, situations, and sociopolitical agendas. “Both historical contextualization and the assignment of authorship are acts to limit the scope of interpretation,” he noted in describing the activities of ancient commentators.

On the second day, Prof. Xu Jianwei (Renmin University of China) began tracingthe development of early Chinese texts, and how they were molded by the commentary traditions of later generations. The Zhuangzi edition used today, for instance, has 33 chapters based on the commentary of Guo Xiang (late 3rd century CE), while the earlier edition by Liu Xiang (late 1st century CE) had 54 chapters. However, after Liu Xiang’s editorship at the imperial court, although certain chapterswere revised in terms of size and sequence, the content of the early philosophical texts did not undergo significant change. This is mainly due to the fact that annotation and transmission after this date werelargely done under the supervision of the central government. While since medieval times, many ancient commentaries were produced separately from the central texts, these commentaries did not fundamentally change the classics themselves.Moreover, it was only then that the classics and their commentaries were compiled together; in ancient times, they had always remained separate works. Continuing Kern’s earlier focus on the Shijing,Xu presented fascinating findings from his work on a new edition of the classic that he is currently co-authoring. He pointed to important Japanese scholarship from the early 20th century that had established the very early date of the character dictionary Erya(“Approaching Elegance”), a work whose first three chapters may predate Confucius. Xu explained how even the Mao commentary to the Shijing, dating fromthe Han dynasty,contained traces of this extremely ancient scholarly tradition, despite the fact that at the time, the Shijingitself was at least in part transcribed from memory.

Wednesday was devoted to Prof. Glenn W. Most (ScuolaNormaleSuperiore di Pisa)and the topics of Homer in Greek culture, paratexts, critical editions, and etymology. Most explained the early history of the Homeric epics from oral to written texts, and how by the fifth century BCE, the ancient Greeks could not conceive of their classical texts without thinking of particular authors (a striking difference to ancient China). While Homer never named himself in the Iliad or the Odyssey, Hesiod was the first Greek poet who did in his Theogony.Next, showing images of ancient and medieval manuscripts, Most introduced paratexts, that is, the texts that surround a central text (title, the name of the author, commentaries, etc.), where he distinguished “systematic”from “sporadic”paratexts: while sporadic comments could be written together with the text of the classic, systematic commentarieswere not written on the same manuscript roll. From this, Most concluded that the reading of an ancient Greek text together with its commentary required not one person but at least two, who read not silently but together and aloud. While this matches the situation in ancient China where texts and commentaries were written as separate works, in medieval texts from China—for example, Dunhuang manuscripts—texts and paratextswere written together, with the paratext sometimes, by later copyists, becoming confused with the classic itself. In the final part of his lecture, Most discussed the question of allegoresis, a particular interpretation of the Greek classics, including Homer, where certain passages were “decoded” as meaning something altogether different—once again a fruitful observation that allowed for productive comparisons with ancient China.

The final lecture on Thursday, June 22, was given by Prof. Denis Feeney (Princeton University) who introduced Latin canons and commentaries, and the importance of the Greek commentary tradition to the formation of Latin literature. As Feeney pointed out, after the Greeks the Romans were the only ones in Western antiquity who developed their own literature, startingin 240 BCE with the first translation of a text from Greek into Latin. From then on, Roman literature and Roman commentary always followed the Greek model, and in later (medieval) times was even seen as the successor of Greek literature because the latter declined just at the time when the former began to develop. Most interestingly, Roman literature developed radically different from both Greek and Chinese literature: not under the sponsorship of the imperial state (China) or a king (Greece, with the royal library of Alexandria), but entirely by individual authors whose work was sponsored by prominent patrons. In most cases, these extraordinary individuals were not originally Roman citizens but came as multilingual foreigners to Rome where they worked as slaves, servants, or tutors to their patrons. Before Roman literature developed in this way, no other culture in Western antiquity had translated literature; in fact, according to Feeney, before the Roman Republic “literature is what does not get translated.” Thus, nobody had translated the ancient Mediterranean or Near Eastern works of literature before they were finally translated into Latin. In conclusion, Feeney introduced the students to a particular commentary, namely, Servius’ 4th century commentary on Virgil’s Aeneid, where he reviewed in detail the elements of Roman textual scholarship.

Following the four days of lectures, a full day was given to the students to present their own work in light of what they had learned over the course of the week. As they did so in small groups each led by one of the four instructors, they received comments and professional advice from both the professor and their peers. The workshop concluded with another plenary session on Saturday where the four professors recalled the important themes of the week and recognized both the smooth organization by Renmin University and the wonderful contributions of the students throughout the week. The next such workshop for Ph.D. students from around the world, again hosted at Renmin University of China by its International Center for the Study of Ancient Text Cultures, will take place in January 2018. Then, the topic will be “Manuscripts and the Materiality of Texts,” with scholars covering ancient and medieval China, Egypt in Late Antiquity, and the medieval Latin tradition.